Breast Cancer: When Good DNA Goes Bad

It’s likely that everyone has had cancer impact them in one way or another. The entire month of October, in fact, is dedicated to an awareness of breast cancer. One in eight women will be diagnosed with breast cancer in their lifetime. Sometimes, however, “awareness” falls short of the real goal: education. It’s important that teachers and students are not only aware of breast cancer, but understand that there are varied types of breast cancer that must be treated differently and with special techniques. The TI STEM Behind Health activity called “Breast Cancer: When Good DNA Goes Bad” follows the personal cancer ordeal of Kristi Egland, Ph.D., a researcher who was diagnosed with the same type of cancer that she was researching. Read Egland’s story and learn about one woman’s journey from diagnosis to treatment to cure. October is the perfect time to explore this very important topic in the classroom.

“Kristi, you have stage 3 Triple Negative Invasive Ductal Carcinoma.”

The condensed version of that diagnostic statement would be, “Kristi, you have breast cancer.” But the grim news didn’t have to be watered down or interpreted for Egland. You see, as a researcher at Sanford Research in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, Egland’s job at the time was researching the very type of breast cancer with which she had just been diagnosed. She knew what it meant, and her initial thought was, “I’m gonna die.” Spoiler alert: She didn’t die. However, there were certainly moments in the months that followed when she felt as if that would be preferable to the agony she was enduring. Yet, Egland certainly had something to live for. Three “somethings,” in fact. Her husband and two young children were with her when she was diagnosed with her cancer, and they were with her throughout the treatment and recovery ordeal. They were worth fighting for and living for. And fight, she did, with aggressive, multipronged action. Because Egland knew that getting aggressive with “The Aggressor” could be the only course of action that would save her life.

Egland’s breast cancer story is shared for all to see in the Texas Instruments STEM Behind Health activity called “Breast Cancer: When Good DNA Goes Bad.” This classroom activity will quickly pull your students into her emotional story and have them investigating the exponential growth of breast cancer cells to gain better understanding of the genetics of the disease. This TI-Nspire™ problem-based learning simulation takes students inside the real world of cancer research, diagnostics and treatment.

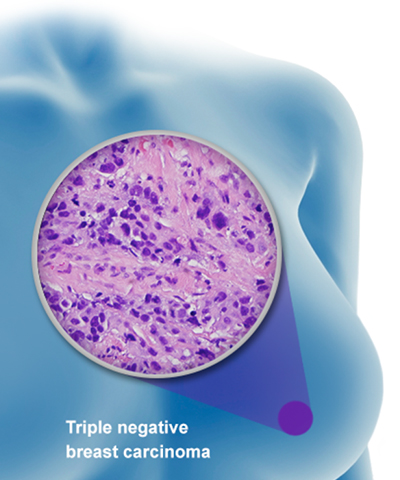

At present, around a dozen different types of breast cancer have been identified. So, when we refer to “cancer,” we really should make the word plural. While no type of breast cancer is to be taken lightly, statistics (and biology) show that the “triple negative” varieties are especially tough to deal with because of their relentlessly aggressive natures and difficulty to treat. Most cells in your body have specialized protein molecules, called receptors, on their surfaces. Think of a receptor as a sort of satellite dish that has a very specific job. For example, one of the best-known and well-studied cell membrane surface protein is the insulin receptor, which, not surprisingly, responds to the hormone insulin. Insulin is secreted into the bloodstream by the pancreas, the insulin bumps into one of its special receptors, a door in the cell membrane opens, and blood sugar (glucose) leaves the bloodstream and enters the cell. If there’s no insulin — or a messed-up insulin receptor — glucose can’t get into the cells, so it stays in the bloodstream and that leads to “high blood sugar” and maybe diabetes. (By the way, another awesome activity available on the TI website is called “Type 1 Diabetes: Managing a Critical Ratio.” Check it out!)

Okay, back to the triple negative aspect of breast cancer. The “triple” part, not surprisingly, means that there are three separate types of receptors that are absent from the surface of breast cells. Three receptors that are not there = “triple negative.” Two of these three receptors will sound familiar to you, I’m sure. They are receptors for the hormones estrogen and progesterone. The third receptor is called the “HER2” (human epidermal growth factor receptor), which responds to a protein (HER2, by chance) that stimulates normal cell division and growth. The reason that “triple negative” is a big deal is because one of the most effective means of treating breast cancer is to link treatment molecules (in other words, chemotherapy) to hormones like estrogen and progesterone. Are you starting to get the picture? No receptors mean no way for the hormones to locate their specific satellite dishes and no way to get the treatment drugs into the rogue cancer cells. Bottom line? Triple negative breast cancers are the toughest to treat and toughest to beat.

Egland knew this as the diagnosis was crossing the lips of the pathologist who was charged with sharing the tough news with her. Her work life had just become her personal life. She responded with force and with fortitude. Egland chose to undergo a procedure called a double mastectomy, a surgery that removes both breasts, and several lymph nodes were also removed during the procedure. After a short, excruciating recovery from surgery, Egland endured eight rounds of chemotherapy and 33 rounds of radiation therapy. She was literally in a fight for her life. Because of the advanced stage of her cancer, Egland had to pursue an extremely aggressive treatment to increase her chances of survival. As the days crawled by, brutal side effects started creeping in. The chemotherapy that was intended to kill cancer cells also destroyed other fast-growing cells, causing Egland’s hair to fall out. Egland’s fingers and toes also lost their sensitivity, and she experienced exhaustion. The chemotherapy caused some of her chest muscles to get intensely tight and sore. As anybody likely would, she started to lament, “Why me!”

It’s been said that all cancer is genetic. And some cancer is hereditary. No, that is not redundant. “Genetic” refers to DNA, and all cancer has something to do with “good DNA going bad.” DNA directs the production of proteins, and you can produce thousands of different proteins. Some of these proteins have the job of keeping cell division under control.

try to replicate DNA without error.

When DNA gets changed or damaged, the proteins that are produced may not work correctly. When cell division rages out of control, cancer can result. So, what about the hereditary part? Hereditary means that you may have a higher likelihood of developing certain cancers because that type of cancer is present in your family. Breast cancer has a potential hereditary component to it. Still, even though certain types of cancer may “run in your family,” there are steps you can take to reduce the risks. If you’re a parent and/or teacher, it’s important to remind children of this. Lifestyle choices are so important. If you don’t smoke, exercise regularly, and maintain healthy eating habits, you can reduce the likelihood that you will mutate DNA and develop cancer. Tobacco use is a direct cause of nearly 1/3 of all cancer deaths!

If a malignancy (a “spreading” type of cancer) does develop, as was the case with Egland, it’s important to remember that teams of professionals work together to help. Sometimes TV shows and movies depict one person as a do-all worker of medical miracles. On the contrary, specialists in radiology, surgery, pathology, reconstruction, chemotherapy, radiation therapy and genetics all work together. In addition, nurses, lab technicians, physicians and other professionals all commit themselves to the individual requiring care. The work of these heroes helped Egland slowly turn the corner from despair to hope. Despite the physical, mental and emotional tolls that beat Egland down day after day, week after week, she stayed positive. Eventually, each checkup brought miraculous news of a body that appeared to be free from cancer!

When the treatments were finally over, she asked herself, “Why did it work for me? How can I use my struggle to help others?” Teams at Sanford Research are working with scientists around the world to discover new approaches to prevent and treat cancer.

Using her experience as a patient, Egland leads a research team who studies breast cancer from the lab bench.

Others lead clinical teams who work directly with patients. Both are advancing our understanding of cancer and working toward personalized cures for this disease. Breast cancer is different for each person who is diagnosed, and treatments are specific for each patient. If Sanford researchers can determine mutation patterns in cancer cells, more specific and effective breast cancer treatments could become a reality and save countless lives.

Consider taking classroom time this October, the month of Breast Cancer Awareness, to cover this important topic with your students. Education is key, and TI makes it easy to explore the topic by providing downloadable student files, calculator files and teacher notes too. TI and Sanford Health’s cancer researchers and medical professionals designed this innovative activity to be appropriate for both middle grades and high school students and encourages them to make meaningful connections by exploring, observing and reasoning with science and mathematics.

Intrigued and want to learn more? Be sure to check out the webinar I recently presented, which is now on demand, for more information on using this activity in your classroom.

About the author: Jeff Lukens spent 35 years as a high school biology teacher, retiring from the classroom in 2014. Currently, Lukens works with science teachers and their students on the implementation of TI technology in the classroom, as well as doing presentations at local, state and national conferences.

Tagcloud

Archive

- 2026

- 2025

- 2024

- 2023

- 2022

-

2021

- January (1)

- February (3)

- March (5)

-

April (7)

- Top Tips for Tackling the SAT® with the TI-84 Plus CE

- Monday Night Calculus With Steve Kokoska and Tom Dick

- Which TI Calculator for the SAT® and Why?

- Top Tips From a Math Teacher for Taking the Online AP® Exam

- Celebrate National Robotics Week With Supervised Teardowns

- How To Use the TI-84 Plus Family of Graphing Calculators To Succeed on the ACT®

- AP® Statistics: 6 Math Functions You Must Know for the TI-84 Plus

- May (1)

- June (3)

- July (2)

- August (5)

- September (2)

-

October (4)

- Transformation Graphing — the Families of Functions Modular Video Series to the Rescue!

- Top 3 Halloween-Themed Classroom Activities

- In Honor of National Chemistry Week, 5 “Organic” Ways to Incorporate TI Technology Into Chemistry Class

- 5 Spook-tacular Ways to Bring the Halloween “Spirits” Into Your Classroom

- November (4)

- December (1)

- 2020

- 2019

-

2018

- January (1)

- February (5)

- March (4)

- April (5)

- May (4)

- June (4)

- July (4)

- August (4)

- September (5)

- October (8)

-

November (8)

- Testing Tips: Using Calculators on Class Assessments

- Girls in STEM: A Personal Perspective

- 5 Teachers You Should Be Following on Instagram Right Now

- Meet TI Teacher of the Month: Katie England

- End-of-Marking Period Feedback Is a Two-Way Street

- #NCTMregionals Kansas City 2018 Recap

- Slope: It Shouldn’t Just Be a Formula

- Hit a high note exploring the math behind music

- December (5)

- 2017

- 2016

- 2015